How does cortisol affect metabolism?

When we think about weight loss, we often focus on calories, workouts, or the latest trendy diet. But there’s a powerful hormone quietly working behind the scenes that can either support or sabotage your goals: cortisol.

Cortisol is also known as the stress hormone. Understanding the relationship between stress and weight loss isn’t just about managing your emotions; it’s essential for unlocking long-term metabolic health.

Let’s explore how stress affects your metabolism, the difference between healthy and harmful stress, and how to support your body in burning fat efficiently, especially around your mid section.

Not all stress is bad: hormetic vs. chronic stress

Stress often gets a bad rap, but it’s not always the enemy. In fact, certain types of stress can actually benefit your body when they’re brief and well-managed. This kind of productive stress is known as hormetic stress. It gives your system a short, controlled challenge that strengthens your resilience over time [1].

Hormetic stress might show up as nerves before a big presentation or before starting a new job, or the hustle of moving to a new home. These situations briefly elevate cortisol, helping you focus, stay alert, and rise to the occasion. Once the event passes, your cortisol naturally drops, and your body returns to baseline, ready to recover and grow stronger.

The real trouble begins when stress persists and becomes chronic. This chronic form of stress can wear down your system, and includes:

- Constant worry, anxiety, or mental overload

- Overstimulation from screens, notifications, and noise

- Endless doom scrolling and media overload

- Decision fatigue from multitasking all day

When your body is stuck in this state for too long, cortisol levels can stay elevated, disrupting everything from blood sugar balance to sleep quality. Over time, this can contribute to insulin resistance, obesity, [2] increased cravings [3], fatigue, poor metabolic function, and perhaps most noticeably, the accumulation of stubborn belly fat.

How chronic stress affects weight loss and cortisol

Cortisol’s job is to help you respond to stress. It raises blood sugar, increases blood pressure, and shifts your metabolism to prioritize the use of quick-burning fuel like carbs so you can take action [4].

In small bursts, this is helpful. But when cortisol remains high for extended periods, like in people dealing burnout, chronic stress, or poorly controlled diabetes, it creates a metabolic imbalance [5].

Here’s what happens when cortisol is consistently elevated:

- Increased belly fat: Chronically high cortisol levels signal your body to store more visceral fat (the kind that surrounds your organs), particularly in the abdomen [2].

- Impaired fat-burning: Your mitochondria become more reliant on carbohydrates and less efficient at burning fat for fuel [4]. This reduces your metabolic flexibility, or how efficiently your mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, switch between burning carbs and fats for fuel.

- More cravings: Cortisol stimulates appetite and cravings, which can lead to weight gain over time if eating in a caloric surplus [3].

- Blood sugar imbalances: Chronically elevated cortisol raises glucose levels. The pancreas compensates by secreting more insulin. Over time, constant insulin exposure desensitizes receptors and signaling pathways, potentially causing insulin resistance. [6].

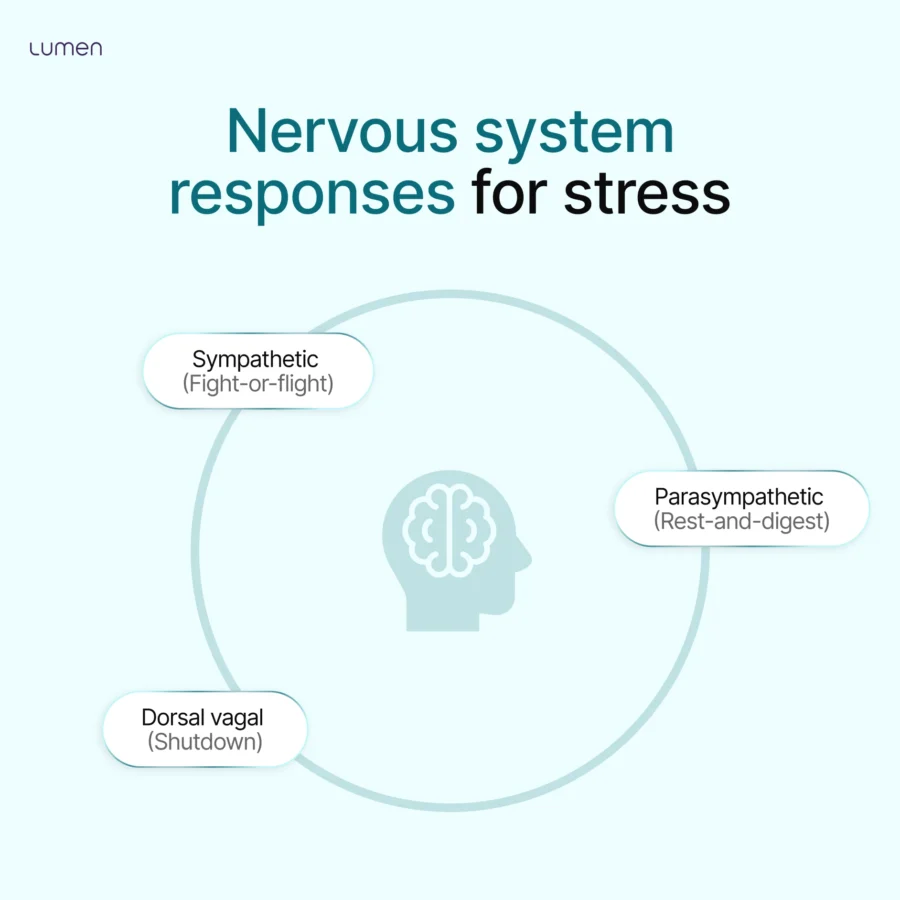

Nervous system responses to stress

Your nervous system has three central response systems, sympathetic, parasympathetic, and dorsal vagal, each with a different metabolic impact.

These responses are part of your autonomic nervous system, which automatically regulates vital functions like heart rate, digestion, and respiration.

Depending on the type and intensity of stress, your body can shift between different states that either support or hinder metabolism and energy balance [7].

- Sympathetic (Fight-or-flight)

This is your body’s alert system. Cortisol and adrenaline increase to help you react quickly. Your heart rate rises, digestion slows, and blood sugar spikes for quick energy.

- Parasympathetic (Rest-and-digest)

Also called the ventral vagal response, this mode promotes calm, safety, and recovery. It supports digestion, nutrient absorption, and fat metabolism.

- Dorsal vagal (Shutdown)

When stress becomes overwhelming, your body can enter a “freeze” state. You may feel numb, fatigued, or checked out. This state conserves energy but impairs metabolic function and motivation.

What is the vagus nerve?

The vagus nerve is key in regulating the parasympathetic nervous system [8]. It runs from your brainstem to your gut, influencing heart rate, digestion, and mood. Just like your muscles, it has a “tone.”

- High vagal tone = better mood, reduced inflammation, more efficient stress recovery.

- Low vagal tone = increased risk of anxiety, depression, and poor metabolic health.

One way to measure vagal tone is through heart rate variability (HRV), which is the variation in time between heartbeats. Higher HRV is linked to better emotional resilience and metabolic flexibility.

Adaptive vs. maladaptive stress coping

How we respond to stress matters just as much as the stressor itself.

Adaptive coping strategies build resilience and help lower cortisol levels naturally:

- Meditation and mindfulness

- Breathwork

- Physical activity

- Journaling or creative expression

- Social connection

Maladaptive coping strategies may offer short-term relief but worsen stress over time:

- Alcohol or substance use

- Emotional eating

- Avoidance and procrastination

- Excessive screen time

- Angry outbursts or impulsive behavior

If your goal is sustainable weight loss, it’s crucial to recognize when you’re reaching for unhealthy coping mechanisms and gently guide yourself toward healthier ones.

“What I liked about Lumen was that it was looking at overall health versus just weight loss.”

—Maria Fox, 52, England, Lumen User

How to naturally balance your cortisol levels

You don’t need a total life overhaul to bring cortisol back into balance. Instead, support your body’s natural rhythm with small, consistent shifts. Here are some evidence-based strategies:

1. Get morning sunlight

Starting your day with sunlight, ideally within 30 minutes of waking, helps reset your internal clock and support healthy cortisol rhythms. Cortisol should peak in the morning and gradually taper off throughout the day. Morning light exposure enhances this natural cycle, improving alertness, energy, and sleep quality later in the night [9].

2. Cut back on caffeine

A little caffeine can give you a helpful boost, but too much, especially later in the day, can overstimulate your nervous system and mimic a stress response. High caffeine intake may increase cortisol levels, especially when you’re already feeling overwhelmed. If you’re prone to anxiety or poor sleep, scaling back your intake in the morning can help keep your stress hormones in check [10].

3. Eat tryptophan-rich foods

Tryptophan is an amino acid that helps your body produce serotonin, a neurotransmitter that regulates mood, sleep, and stress. Including turkey, eggs, oats, and seeds can help support a more relaxed state and enhance your ability to manage daily stressors [11]. This can also contribute to a more balanced cortisol profile over time.

4. Limit alcohol

Alcohol can feel like a quick way to unwind, but it often backfires. It disrupts sleep, raises nighttime cortisol levels, and interferes with fat metabolism, especially around the belly. Regular alcohol intake can also dysregulate your HPA (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) axis, leading to a prolonged stress response and greater emotional reactivity [12].

5. Move your body

Low-impact exercises like walking, yoga, or cycling are great ways to reduce stress and anxiety without overloading your system [13]. High-intensity workouts can temporarily raise cortisol levels (which isn’t always bad), but when you’re already under chronic stress, gentler exercise can help calm your body. Even a short outdoor walk has been shown to lower stress and improve mood.

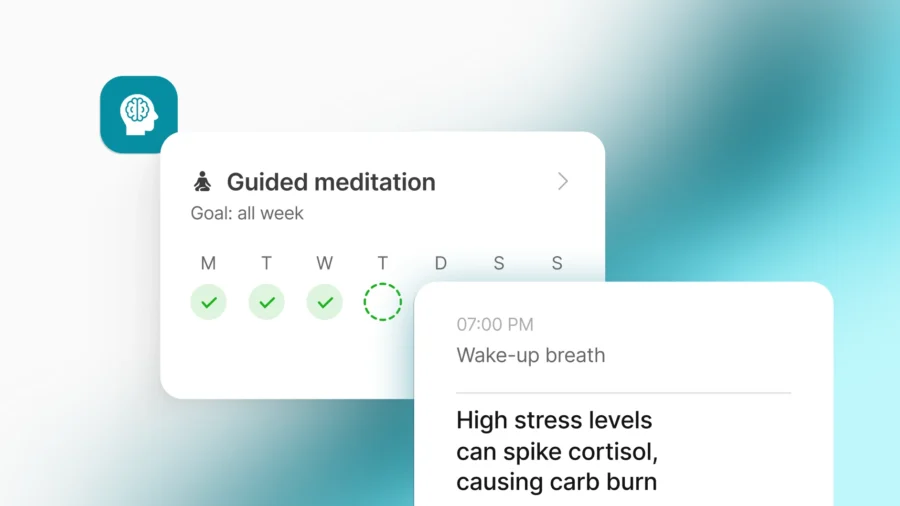

6. Practice breathwork and meditation

Slow, deep breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system, encouraging “resting and digesting, and helps your body recover from stress. Deep breathing practices or guided meditations can improve vagal tone and lower cortisol levels over time [14].

7. Spend time in nature

Spending time in nature or grounding, walking barefoot on grass or soil, has calming effects on the nervous system. This simple practice can improve sleep, lower cortisol, and boost positive mood [15, 16].

8. Supplement wisely

Certain supplements can help your body become more resilient to stress. Magnesium supports nervous system relaxation and better sleep quality [17], both essential for keeping cortisol in check. Rhodiola rosea, a well-studied adaptogenic herb, helps your body adapt to physical and emotional stress while reducing fatigue and improving performance under pressure [18].

Cortisol: friend or foe?

Cortisol isn’t the enemy; it’s part of how your body keeps you alert, energized, and resilient in the face of stress. In short bursts, it can be beneficial, helping you push through a tough workout, tackle a deadline, or stay focused under pressure.

But when stress becomes your baseline, cortisol shifts from helpful to harmful. Over time, elevated levels can impair your mitochondria, disrupt fat metabolism, and leave you feeling drained, hungry, and stuck in a cycle of weight gain.

It’s not about eliminating stress but building habits that help your body handle it effectively. By supporting your nervous system, building resilience, and making mindful lifestyle choices, you can keep cortisol in balance, optimize mitochondrial health, and finally break free from the cycle of stress and unwanted weight gain.

Sources

- Oshri, A., Cui, Z., Owens, M. M., Carvalho, C. A., & Sweet, L. (2022). Low-to-moderate level of perceived stress strengthens working memory: Testing the hormesis hypothesis through neural activation. Neuropsychologia, 176, 108354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2022.108354

- Steptoe, A., Kunz-Ebrecht, S. R., Brydon, L., & Wardle, J. (2004). Central adiposity and cortisol responses to waking in middle-aged men and women. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 28(9), 1168–1173. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802715

- Epel, E., Lapidus, R., McEwen, B., & Brownell, K. (2001). Stress may add bite to appetite in women: a laboratory study of stress-induced cortisol and eating behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 26(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00035-4

- Thau L, Gandhi J, Sharma S. Physiology, Cortisol. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538239/

- Eisner, V., Picard, M., & Hajnoczky, G. (2018). Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses. Nature Cell Biology, 20, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41556-018-0133-0

- Myriam, B., Nacef, I. B., Essayeh, S., Mekni, S., Laamouri, R., Karima, K., & Imen, R. (2025). Long-term impact of hypercortisolism on diabetes outcomes: A follow-up study. Endocrine Abstracts. https://doi.org/10.1530/endoabs.110.p173

- Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, et al. Physiology, Stress Reaction. [Updated 2024 May 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

- Goggins, E., Mitani, S., & Tanaka, S. (2022). Clinical perspectives on vagus nerve stimulation: present and future. Clinical science (London, England : 1979), 136(9), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20210507

- Blume, C., Garbazza, C., & Spitschan, M. (2019). Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie : Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin = Somnology : sleep research and sleep medicine, 23(3), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x

- Sabt, A., Alyafei, F., Alaaraj, N., Hamed, N., Ahmed, S., & Soliman, A. (2025). Cortisol response to coffee, tea, and caffeinated drinks: A Comparative Review of Studies. Endocrine Abstracts. https://doi.org/10.1530/endoabs.110.p151

- Friedman M. (2018). Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. International journal of tryptophan research : IJTR, 11, 1178646918802282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646918802282

- Friedman M. (2018). Analysis, Nutrition, and Health Benefits of Tryptophan. International journal of tryptophan research : IJTR, 11, 1178646918802282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178646918802282

- Ma, J., Lin, P. & Williams, J. Effectiveness of nature-based walking interventions in improving mental health in adults: a systematic review. Curr Psychol 43, 9521–9539 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05112-z

- Fincham, G.W., Strauss, C., Montero-Marin, J. et al. Effect of breathwork on stress and mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised-controlled trials. Sci Rep 13, 432 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-27247-y

- Kondo, M. C., Jacoby, S. F., & South, E. C. (2018). Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health & place, 51, 136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.03.001

- Ewert, A., & Chang, Y. (2018). Levels of Nature and Stress Response. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 8(5), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8050049

- Zhang, Y., Chen, C., Lu, L., Knutson, K. L., Carnethon, M. R., Fly, A. D., Luo, J., Haas, D. M., Shikany, J. M., & Kahe, K. (2022). Association of magnesium intake with sleep duration and sleep quality: findings from the CARDIA study. Sleep, 45(4), zsab276. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab276

- Ivanova Stojcheva, E., & Quintela, J. C. (2022). The Effectiveness of Rhodiola rosea L. Preparations in Alleviating Various Aspects of Life-Stress Symptoms and Stress-Induced Conditions-Encouraging Clinical Evidence. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(12), 3902. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27123902

Digital download

Digital download